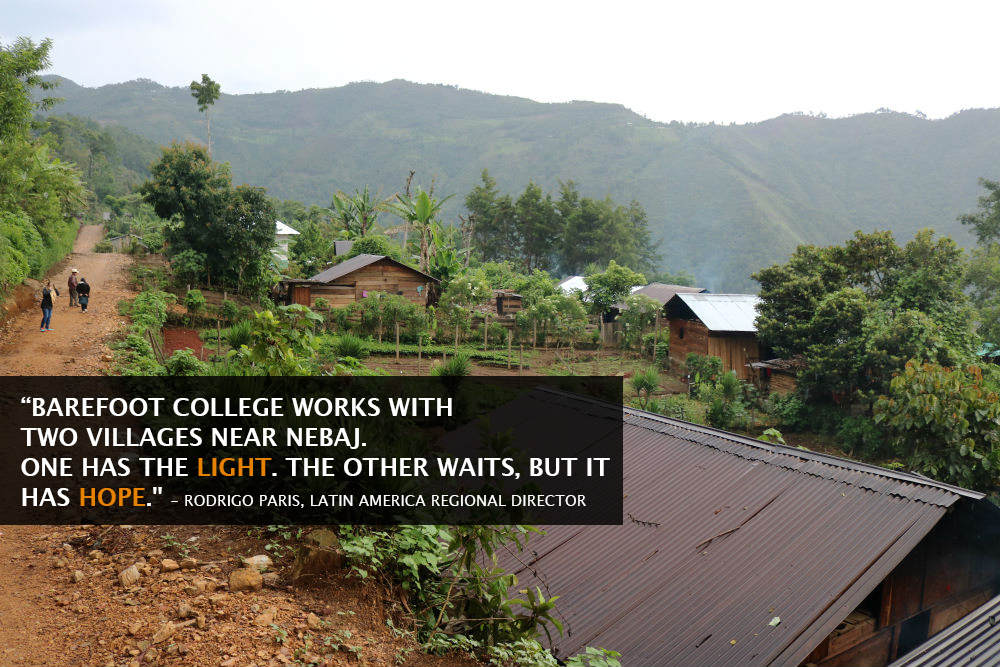

Two villages on opposites sides of the northern Guatemalan city of Nebaj have almost everything in common.

Both Pal and Xecotz, villages in one of the world’s most inspiring rain forests have been stewarded by the indigenous people of the country who identify themselves as Ixil Mayans. Women wear traditional clothes. Homes are made of shiplap. Cooking and heating are mostly done on a brick stove that burns wood. Floors of dirt are swept clean and neat. What water there is, flows from questionable sources.

Work is hard to come by, and even the most basic supplies require a treacherous journey over a steep, riveted dirt road back to Nebaj. These rides are made on cramped “chicken buses” or on the bed of a passing pick-up truck. Either way, they leave the riders roughed up by the journey. Residents have good humour and an evident sense of community, but there is no denying that life is hard for the Ixil people in the villages of Pal and Xecotz.

We came to these villages at the request of Semilla de Sol, a local NGO supporting the needs and civil rights of indigenous communities, to recruit mamas to train with us and become solar engineers of their villages.

“Here, 40 percent of the population is indigenous,” Rodrigo Paris, Barefoot College Latin America Regional Director says. ”Our idea, not only in Guatemala but in Latin America, is to work with the indigenous villages to empower people to recover their ancestral knowledge and show them other opportunities for sustainable environments and economic hope.”

The two villages do not share one critical thing:

- P’al has solar-powered light installed by Catarina, a mother chosen by her village to be trained at Barefoot College in India and become a Solar Mama.

- Xecotz, is waiting. While having also trained two native solar mamas; Magdelena and Elena need equipment that will launch their careers and electrify their village.

“One has the light,”

Rodrigo says.

“The other has hope.”

Juan is the president of the Council of Xecotz. He knows how much the light will benefit the community. He doesn’t know when it will arrive, but he refuses to be discouraged.

“We want that solar equipment,” he says. “We send our petitions to the state like they have never seen before… Right? This, with Barefoot College, is where the idea was born. We need to help make it a reality.”

Juan, president of the Xecotz Council

Juan, president of the Xecotz Council

Light comes first

We’ve been working in Guatemala since 2012. With six projects in indigenous communities, 80% of them with the Ixil population in the department of El Quiché. More than 300 families have received electrification in their homes due to solar panels and the newfound wisdom of 12 Solar Engineers trained in India to inspire the young and old that anything is possible.

“Light is everything,” Paris says. “When a village has light they can make a significant change after decades where nothing has changed.”

At Barefoot College we use our solar electrification program to begin a comprehensive effort to raise people out of extreme poverty. Solar Mamas return to their villages to bring the light. They also help educate about environmental sustainability and economic opportunity they learned while on campus. Once light is available, education opportunities for children can follow as proven in India with the Digital Night Schools.

“These people see that there are other opportunities for sustainable living for them in these types of environments,” Paris says. “They don’t need to go to the cities. In these places they are going to find opportunities, hopes and dreams for generations.”

Progress where light shines

The impact is evident in P’al, where 100 homes have been solar electrified. Residents of Pal interviewed six months after solar panels were installed were enthusiastic about its impact. They reported reduced kerosene use, saved money and more productive time in the evenings.

“Our partnership with Barefoot College has worked very well,” said Baltezhar, a resident of P’al and regional committee member of Indigenous Communities of Nebaj. “The solar program is benefitting the entire community. We are very grateful.”

The program is not without obstacles. A solar committee composed of three women and two men are responsible for collecting fees from each home as remuneration for having solar power. This is how the Solar Mama is paid for the installation and consistent upkeep. The process takes some degree of education. Misunderstandings can arise.

During a recent visit, Rodrigo and Baltezhar joined the P’al town council for a meeting to dispel rumours about the program and encourage people to pay for their services. Payments to the solar mama in their town had lagged. It’s a collective effort and communication is key.

“This is their program,” Paris says. “They are empowered to keep it alive. We can only guide them along the way.”

For Xecotz, the lack of a donor or government assistance for the equipment has also delayed the work, but Elena and Magdelena are hopeful… and resolved. Both women survived the atrocities of the civil war in Guatemala. Today, in full vitality, they are ready to transform their lives and their village.

“I’d like to do what I learned,” said Magdalena. “I can use the income and the light will be good for the village.”

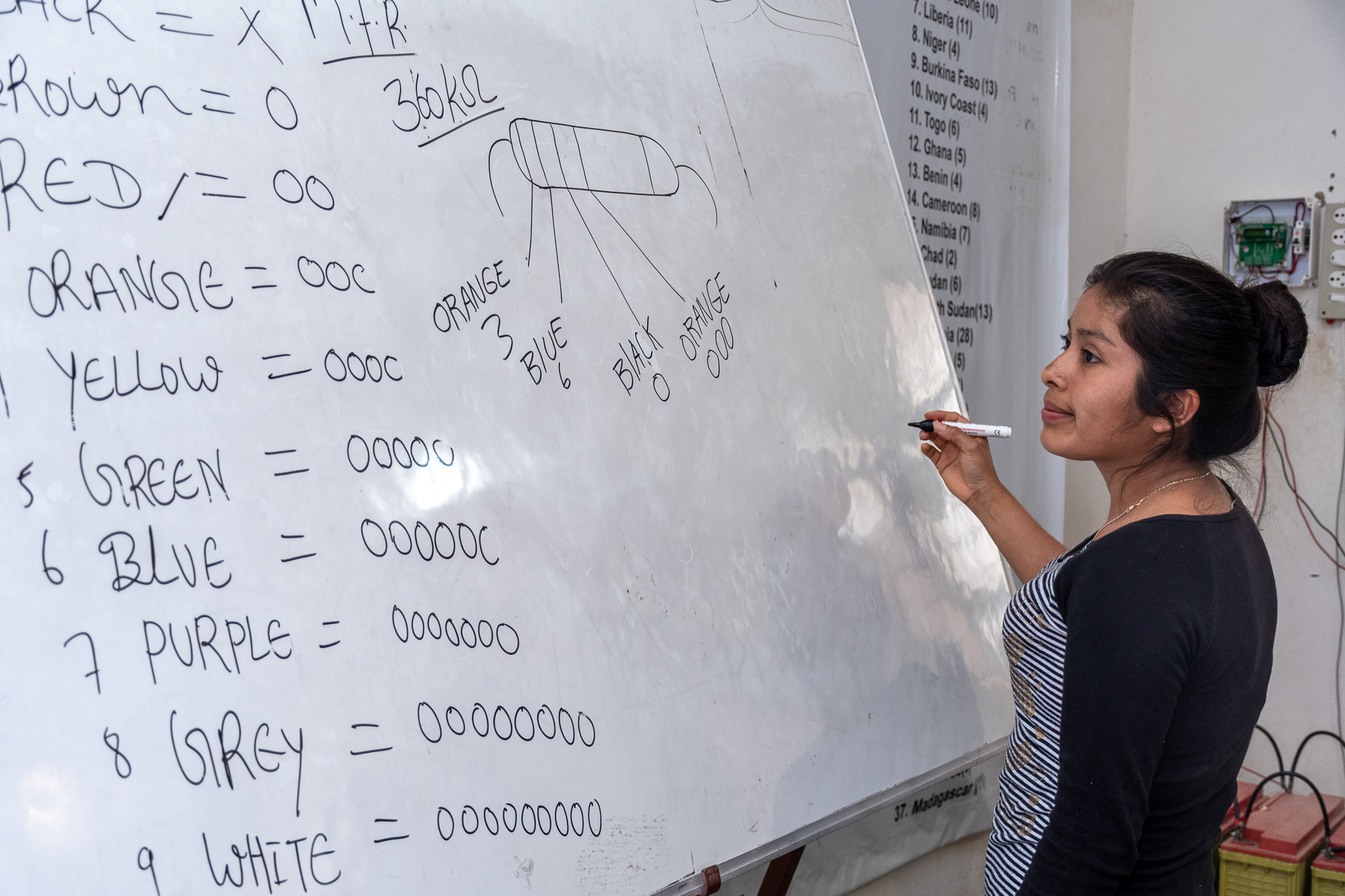

Juana De Leon from the village of Xecotz learning to identify resistors and capacitors required for assembling solar circuit boards

Juana De Leon from the village of Xecotz learning to identify resistors and capacitors required for assembling solar circuit boards Juana in solar class taking notes with peers from Peru

Juana in solar class taking notes with peers from Peru Catarina Santiago Matón, resident and Solar Engineer of the village of P’al

Catarina Santiago Matón, resident and Solar Engineer of the village of P’al Solar Mamas Magdalena and Elena with their friends at a town council meeting in Xecotz to discuss progress on getting the needed equipment to solar electrify their village.

Solar Mamas Magdalena and Elena with their friends at a town council meeting in Xecotz to discuss progress on getting the needed equipment to solar electrify their village.

Perched at the top of a mountain, the village of Xecots resides without access to grid or solar power.

Perched at the top of a mountain, the village of Xecots resides without access to grid or solar power.